Priory 900 and an exploration of the Herefordshire School of Romanesque Sculpture at Leominster Priory, June 14th to July 14th 2025.

Stitched Atlas Folk is a Community of Practice who have been working together since September 2023 responding to local place through its heritage using walking and stitching methods. We meet regularly to discuss personal research findings and to create stitched and storied outcomes. The beauty of the group is that no stitching experience is required, we consider it mark making, which allows a freedom of expression. Our poet Maggie Crompton is both inspired by and documents the group process. She writes: Human beings seem to have been artistic explorers from their earliest existence. Reflecting on their lives, the places and other creatures they see around them and their place in the mystery of what we know as the universe, we have drawn, painted, told stories and sung songs. In Stitched Atlas Folk, we reflect on the past in the present and re-imagine it with needle and with words. The group, also collaborating with Rose Tinted Rags, have three responses planned for the Priory 900.

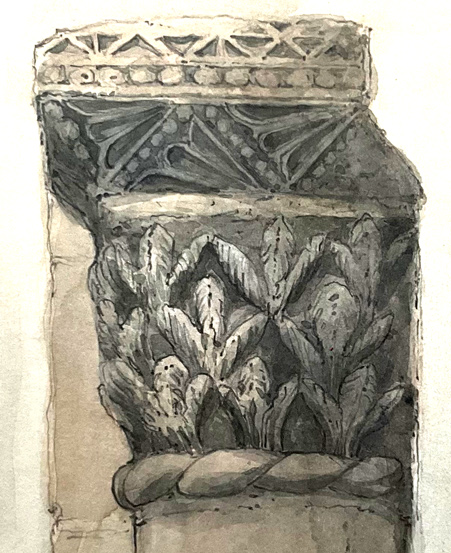

Firstly, we have embarked on creating a large map of the places of the stone carvings of the

Herefordshire School of Romanesque Sculpture, as named by George Zarnecki.

Malcolm Thurlby’s book on the subject has become our new reference work guiding our visits to these places. Our responses to our embodied experiences will be translated through embroidery.

Our second response is to the story of Eadgifu, who was the Abbess of Leominster Priory when it was a Benedictine abbey for nuns. She was abducted in 1046 by Sweyn Godwinson and may have been the same Abbess recorded as living in Fencote in Docklow parish, in the 1086 Domeday Book. We are taking time to explore and reimagine her story in the context of the closely following Norman Conquest, when Anglo Saxon and Norman cultures collided.

Intriguingly, there is a mysterious lady called Aelfgyva in The Bayeux Tapestry, which is a textile panel of 11th century Romanesque art, likely commissioned by William the Conqueror’s half-brother Bishop Odo. In its fifty eight scenes it depicts the story around the Norman conquest and may have been embroidered by English nuns. Aelfgyva is just one of three women making up its 626 characters in its main panel. There are many competing theories as to who Aelfgyva was, and in a 1966 book on The Bayeux Tapestry, her scene was the only one omitted because it was considered to add nothing to the story but a ‘moment of confusion’. The idea that Leominster Priory’s Abbess Eadgifu is one and the same Aelfgyva, has some credence with historians. It is this tangle of stories of Eadgifu & Aelfgyva that have Stitched Atlas Folk hooked!

Our third response is by Rose Tinted Rags who are making an artwork linking and uniting the embroideries of the map with those of Eadgifu & Aelfgyva. They are inspired by the beautiful archway between Aelfgyva and the cleric in their scene in the Bayeux Tapestry. As Aelfgyva’s story appears lost to a moment of confusion, we feel that this archway allows her to travel through time, to mix with all the symbols and motifs of past cultures and present, and to represent all people and all their marvellous stories.